I tried American shops, but they all cut raging high-and-tights, and—on an island where every white male was military—I tried my best to avoid this stereotype. It was a meager rebellion that retained an illusion of independence from the formalities of the Marine Corps. After trying a few American barbers to the same result, I grew desperate until my friend suggested “his” guy—an older Okinawan gentleman named Hiro not far from base. He was a local. I was intrigued.

I pulled my tiny car into the dirt parking lot outside his shop set on a hill that overlooked Kin Bay. The blue water sparkled, reflecting the sun, and an ocean breeze buffeted the hill, gently licking what few strands of long hair I had on my head. His store was packed into a dense cluster of buildings indistinct from one another. Each were formed in the island’s characteristic concrete block mold designed for one purpose—surviving monsoon season—and any Marine who came to Okinawa expecting the traditional triangular roofs of Asia seen in movies was in for a disappointment.

I was nervous as I approached Hiro’s barbershop. Mainly because I barely spoke Japanese—only three phrases actually: hello, thank you, and yes—and feared receiving the dreaded crossed arms gesture the locals sometimes used to ward off Marines. What if I couldn’t communicate the type of haircut I wanted? These and other thoughts danced in my mind as I approached.

I entered the shop to a chime sounded by a small bell attached to the door. A muscular man with a short frame and black hair who I assumed was Hiro casually looked up from cleaning a blade. His face was handsome but one that wore the crease of age and time in the sun, I guessed him to be about 50. To his left stood a woman who I assumed was his wife. She smiled and ushered me to one of two empty chairs in the shop. It was intimate unlike the crowded Marine packed barbershops to which I was accustomed. So far so good, I thought.

Hiro approached and pointed to my head asking me in Japanese what I presumed was, “How would you like your haircut?” I did my best to explain, gesturing to my scalp and sides, while attempting to communicate I didn’t want to look like Mr. Clean when I left. He nodded, examined my head with his hands, and went to work.

Hiro was a craftsman. He cut everything with scissors. And meticulously sculpted in small rhythmic snips as he removed layer after layer of hair with Zen-like concentration. It put me in a hypnotic trance as I relaxed and enjoyed the moment—forgetting about the Marine Corps and coming worries of the week. He finished with a razor shave and head massage, the strength of his fingers kneading away my stress. I'd found Okinawa’s Mozart of barbering.

In Okinawa, I needed a Barber.

The next morning I made the hour-long drive up the coast from Camp Courtney where I lived to Camp Schwab where I worked. It was affectionally called “Forward Operating Base Schwab” by the Marines due to its Spartan nature. The commute was an odd mixture of awe and anxiety as my car traced Kin Bay north, and I gazed at the ocean’s purple-orange beauty as the sun rose over the water. To my left, forested mountains of green jungle jutted into the sky with the occasional collection of structures dotting the lower slopes of the hills. As I drove my mind raced through the tasks of the day, and I anticipated potential ass-chewings and negotiations with senior officers. Okinawa is one of the top scuba diving destinations in the world, a vacation spot for Japan’s elite, but to me it was often ridden with anxiety.

I survived the week and found myself back at Hiro’s shop on Sunday afternoon. The same bell chime and warm smiles greeted me as I entered. It was empty again and I was quickly ushered to the chair. As Hiro cut my hair—the soft sound of snipping filling the silence—I examined the cluttered décor that populated the walls of the barbershop. There were two themes that emerged from this assortment. The first was that Hiro liked golf. Everywhere I looked posters of golfers covered the surface, and an old set of clubs sat in the corner. Tiger Woods, Phil Mickelson, and Jack Nicklaus smiled down at me. This was a good sign for I too enjoyed the sport and had grown up playing—a potential connection to discuss with Hiro. The second theme was bulls, or more specifically, bull fighting. Plastic busts of the animals hung from the wall and various photos of the arena and trophies were proudly displayed. Not to be confused with the more well-known Spanish bull fighting, Okinawan bull fighting involved two bulls facing off against each other. It was less barbaric than the bloody human versus beast contests of Iberia.

There was a stadium not far from my apartment and I used to hear the roar of the crowd on the weekends when I went for my routine run through town. I finally saw a match. A dense audience packed the small arena surrounding a circle of brown dirt. The two bulls—black thousand-pound beasts with muscles rippling from backs and legs were led forth to the center by their Okinawan teams. The coaches wore bright blue and red shirts with large white Japanese lettering splayed diagonally. They locked the horns of the animals and urged them on as the creatures tensed and pushed attempting to subdue the other into ceding ground. The bulls settled into a terse stalemate, legs staked into the ground and dust rising as they threw their weight against the other. The coaches yelled, and we waited for the snap of the pressure to give way. Finally, the bull on my left lowered its head and turned its body. Exhausted from the duel, it submitted to its opponent. The masses cheered, and the match was over.

Only having one experience with bullfighting I chose the more familiar topic of golf and gestured to the clubs and asked, “Do you play?”

“Ah!” he exclaimed, as if too recognizing this was a bridge we could use to cross our cultural divide. “Yes, not good, not good,” he said while shaking his head and laughing. “You play? You good?” he asked. I told him I did but that I too was not very good. We laughed and I pointed to the other side of his wall, “And the bulls?” A look of excitement crossed Hiro’s face and he darted to the wall pulling down a large photograph of himself in front of a bull. He was in a white uniform, flexing an arm while his animal companion towered over him. “I coach,” he said proudly. “Wow, that’s impressive,” I responded.

He asked me my name, which sounded like “Namu?” to my American ears and I told him “Matt.” He nodded, paused, then chuckled and said “Matt Damon. You Matt Damon, very handsome,” and we both laughed at his joke.

I left the barbershop pleased I had connected with my Okinawan barber. He had given me a glimpse into another side of his life as a fellow hack-golfer and adventurous streak as a bull fighter. I wondered if he was well known around the island community for his exploits and victories in the ring.

As the months passed and the seasons alternated between hot and less hot, I integrated Hiro’s barbershop into my weekly routine. On workdays, I’d drive through the Camp Schwab gate, my anxiety rising as I neared my building—a square nondescript box of concrete. As the intelligence officer, I worked in a back corner of our Battalion in a closet-sized office with no windows. Due to my hour-long, one-way commute, I rarely got home before seven at night. My drives back were illuminated by the neon glow of isolated vending machines common throughout the streets of Okinawa. The lack of sunlight in my office and journeys back after sunset made me think I spent more time in darkness than in light. It wore on me.

Often on my drives back, I traveled through a neighborhood where the Okinawan boys would be out late playing baseball in the night. The young pitcher eyeing the batter as he leaned in from his imaginary mound, glove with ball arched behind his back. I slowed my car to a crawl hoping not to disturb the game and perhaps witness the duel about to transpire but the boys stopped and waved me through. The scene was in some ways startling, something I was less accustomed to back home in America. It was as if I was glimpsing through time to the 1950s—no blue glow of cell phones, no helicopter moms screaming for their kids to come inside, no fear about potential kidnappers or criminals on the loose. To the kids there was only the game and heroics of the field. Their parents were at ease knowing their children were where they should be—outside playing.

On the weekends, I often found myself alone driving around Okinawa exploring its various nooks and crannies. I travelled to a small island visible from my apartment on Camp Courtney. It was attached to the mainland by a long bridge. There was a small fishing village I would walk through with delicate houses and gardens lining a waterway canal. If I got there early enough, I’d see the fishing trawlers knifing through the glass-still water on their way out to sea.

Deeper in the island, I stumbled across a secluded beach located in a picturesque cove. I crested a grass hill and saw the sand-covered, crescent moon beach at the bottom of a valley surrounded by cliffs. It was probably a well-known site to the locals, but to me it felt as if I’d found Eden. I hiked to the bottom wondering if I should be there and simultaneously thrilled at my discovery.

The beach became a location of solace, and I spent many Saturdays enjoying its splendor. I’d spend the day swimming and snorkeling, viewing the lush garden of life beneath the surface. Red, yellow, and blue fish darted across the coral and the occasional sea snake gave a jolt of fear as it swam by in its unique zig-zag motion. I’d emerge from the water and sit in the sand letting the warm sun dry me while I stared at the horizon. I knew somewhere far in the distance over the waters was my home and the beaches of Washington, Oregon, and California that I traversed growing up. I thought of my family, and I missed them.

Sundays were filled with dread as the day grew later and another week at “FOB” Schwab loomed, but I always looked forward to my afternoon visit, now a tradition, with Hiro. Somedays when I came in, the TV displayed a Japanese program. It showed couples visiting remote coastal towns on mainland Japan, trying traditional foods, and taking in the sights while conducting game show contests. At various times, he and his wife would laugh at a joke lost in the language abyss. Another time, Hiro watched the local news showcasing the annual Okinawan marathon. The top runners crossed the finish line and collapsed. He nodded his approval, proud of the athletes displaying Okinawa’s physical prowess.

My time in Hiro’s shop was a brief foray into a world I could never truly occupy—a dip of the toe in the pond. I lived my life in the sphere of little America—each base equipped with the familiar mainstays of Taco Bell, Popeyes, and Chilis that offered the illusion of home. The baseball games, bullfights, and barber shop were brief interactions. I skimmed the surface but never submerged.

Hiro and his wife seemed genuinely content. He was a sportsman, good at his profession, and often laughed or joked with his wife and other friends who would sometimes occupy the shop. His job would be considered blue collar in America, yet he seemed happier than most people I’d met. I envied him and the assumed simplicity his life held. Sometimes at work, I’d fantasize about being a garbage man. I’d pick up the trash and go home at days end. Simple. Straightforward. Manual labor.

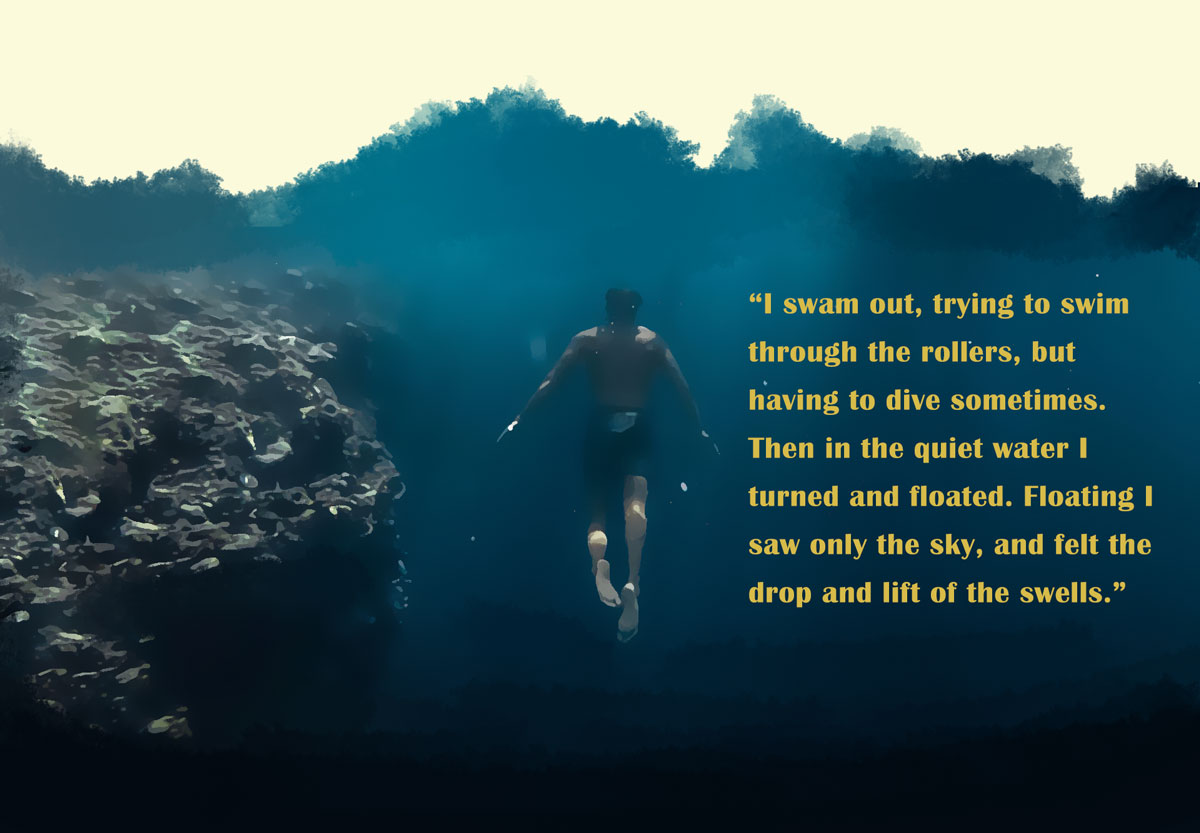

In my loneliness, I retreated to the base library which was rarely occupied. Books had always been a companion and I decided to give Hemingway a try (probably a mistake considering my mental state) having ignored his work in high school. I read “For Whom the Bell Tolls”, “A Farwell to Arms”, and “The Sun also Rises,”—each work brilliant in their prose and ability to convey emotion but lacking hope. Hemingway’s words surfaced in my mind as I swam in the ocean at my secluded beach:

Mentally I could tell I was getting to a strange place. I asked a friend about it. “You’re going through the Okinawa blues,” he said, “it happens to all of us.”

It was as if I was in a time capsule, trapped in a bubble on an island while the rest of the world passed me by. My college friends were living their lives in the great cities of America, like Seattle, New York, and San Diego, while I spent my weeks on repeat like Bill Murray in Groundhog Day. I missed my younger brother's wedding while training in Korea. Tom Brady beat the Falcons and won his fifth Superbowl. The acrimonious 2016 election had the United States in an uproar, but it all seemed distant from my perch on Okinawa.

At night, I’d lie in bed staring at the ceiling wondering when I’d get home. I began to question my belief in God: What was I doing out here? What was the point of this? Why had He directed me to this outcrop in the Pacific where I could drive the length of the island in a few hours? I missed the open roads of home.

I finally returned to the United States for Christmas—the first time I’d been back in a year-and-a-half. Waves of nostalgia hit me as my plane followed the gentle curves of the Columbia River to the Portland airport. It was dark and cold, a shock after living in the constant sunshine of the island. Out of the encouragement of my family, I met with our hometown pastor for lunch and confessed I was losing my faith. He smiled and said, “I think you’re just depressed.” I responded, “I have been a little isolated out there.” And he said, “Well that’s the understatement of the century—you’re living on an island.” He reminded me there was always more happening than we are aware.

In my final days at home, I pondered what my pastor said. I thought about the story of Job. Misery, sorrow, loss; yet there was a bigger conversation occurring that he was never aware of. I thought about the story of Joseph. He spent years in prison while innocent. I thought about the story of Jonah, which ended with a question, not an answer. Maybe I too would never fully understand my time in Okinawa.

I returned to the island determined to reverse my dark outlook on life. But then, a few weeks after I was back I received orders. I was heading to North Carolina in the spring. I was thrilled and set about planning my departure. The months flew by. Soon my final week came.

I made the pilgrimage to my barbershop wanting to have a last haircut with Hiro before I left. It was just the three of us—him, his wife, and me. It seemed quieter in the shop than past trips as if the place itself sensed my departure. Towards the end of the haircut, I spoke up and said, “It’s my final week on the island. I’m leaving Wednesday.” Hiro looked up from a sink where he was washing a blade—slight surprise on his face—and said “Ah, leaving? Very good, very good.” I felt like I should have said something elegant, thanking him for his service, wishing to convey the peace I’d found at his shop but no grand speech came. Instead, I awkwardly thanked him and told him he was the best barber I’d had. He laughed and smiled then said, “Thank you very much.” I paid, waved, and left the shop while Hiro and his wife gave a slight bow.

As I walked across the street towards the dirt lot and my car, I wished I could have expressed my gratitude better. Suddenly, I heard the door open, and his wife ran after me into the street. She held a tiny Shisa ornament, the lion guardian of Okinawa, and thrust it into my hands. “Good luck,” she said, smiled and walked away. The token seemed an indicator that I connected with Hiro and his wife in some way, that it wasn’t some relationship I'd fictionalized in my head. I was glad. I turned and left, knowing I’d never return.

They say Okinawans live longer than anyone else in the world—some combination of community, natural beauty, good food, low crime, and a constant immersion in nature—an odd juxtaposition against the parallel life of American Military stationed on the island. Spending time in Hiro’s shop made me understand why.

I’m firmly back in the United States now and I’ve been out of the Marine Corps for a few years. I have a beautiful wife and daughter, a dog, and a house. I have a great job and good friends. I still golf, I’m part of a church, and I’m learning how to be a father and a husband. I’ve got a good life and I’m thankful to be home. But some days, when I’m stuck in traffic or sitting on the train coming back from work, I daydream, and I think of Hiro’s barbershop.

In my mind I drive along Kin Bay to the hill where his store sits, the sun streaming through the towering clouds—a sky only possible on the island—and I open the door to the familiar ring of the bell and warm smiles that greet me from Hiro and his wife. I sit in his chair facing the bulls and posters of golfers while the quiet snipping of hair fills the air. Sometimes we laugh but mostly we’re silent, him doing his craft, me enjoying the moment, and I realize I miss Okinawa. And that I never saw Hiro bullfight.

Matt Hartley is the cofounder of The Hart and The Cur.

Copyright © 2024 The Hart & The Cur