How did I end up spending a decent part of my twenties traveling to every county in America? It all started with a story my professor shared about the 18th century naturalist and explorer Alexander von Humboldt on a field course I took back in undergrad. “On one of his trips,” my professor said, “Von Humboldt learned that he was traveling with a trained geographer. So, he turned to him and made a sweeping gesture toward the landscape around them, and asked him to read,” he said, gesturing in the same manner toward the landscape in front of us. “If you can read the landscape and discern the human and natural history of a given place, you’re well on your way to being a geographer,” my professor encouraged. I viscerally felt that this form of reading was something that I’d continue doing long after our field course ended. I’d been reading Rand McNally Road Atlases for longer than I’d been reading books and had been attempting to read the landscape since I started biking all over Chicagoland in high school – but to attempt to read the landscape of an entire country would be a much longer endeavor.

Less than a year after my field course, I was as shaken by the results of the 2016 presidential election as anyone who had grown up in inner city Chicago or who now called a college campus in Denver home. The shock felt more personal to me –– my family had taken road and train trips all over the Midwest during my childhood –– and I struggled to comprehend what could have provoked such a profound political shift. Overnight I was grasping to learn all I could, consuming articles, commentary, and books, trying to grapple with why I had suddenly come to feel like a stranger in my own country. Since I was still a full-time student, it was difficult to get away from campus and see what I might be able to learn from the so-called forgotten places people now talked about so much. But I was inspired enough to print off a county-by-county map of the United States, as if to remind myself of the vast number of places in between.

While presenting some of my grad school research at the American Association of Geographers conference in 2019, I learned from another attendee about the existence of the Extra Miler Club, a hobbyist group for people who have a goal of visiting all 3,143 counties in the U.S. I began working a full-time job later that year, and was also finally old enough to rent a car, giving me the ability to travel to the large swaths of the country where private vehicles are the only way to get around. Taking the county-by-county map I’d printed off years earlier, I started coloring in every county I’d been to with an orange highlighter, the ink dense around the upper Midwest and Colorado, while rapidly thinning out in the rest of the country. Staring at the thousand or so counties already highlighted in orange under my belt from my childhood and college years, I decided to make it a life goal to one day travel to them all. With the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic altering the traditional Monday-Friday in-office obligation, I had the rare chance to get off to a running start.

As I set off on my whistlestop tour of the Midwest in the spring and summer of 2020, the most prominent thing to read on the American landscape was evidence of the country’s growing political polarization. Biden-Harris yard signs competed with their Trump-Pence counterparts for attention. As someone who grew up in, and has only ever lived in large cities, the extent of our country’s urban-rural divide increasingly came into focus. While my friends and family members in cities grew ever more confident in their assertions that Trump was on the brink of electoral catastrophe as the pandemic’s death toll soared, the view from state highways in the thumb of Michigan and county roads in western Minnesota painted a very different picture. My mom accompanied me on a road trip to a national park in Ohio that summer, and was visibly aghast when she saw a sign along the state highway (which I’d insisted on taking instead of the interstate) that proclaimed “LIFE – GUN – TRUMP” in all capital letters.

LIFE - GUN - TRUMP

Editor's Note: when Danny completed his journey in 2023 there were only 3,143 counties in the United States. Connecticut eliminated their 8 counties as of Jan 1, 2024, and replaced them with 9 county-equivalent planning regions, increasing the total number by 1.

Danny also sat down with one of our editors for an interview in May 2024. You can watch that conversation here.

Letchworth State Park, New York. Photo by the author.

Sitka, Alaska. Photo by the author.

My confusion in attempting to understand the unraveling of the country’s social fabric only grew as the summer continued. The Black Lives Matter marches on city streets and fierce pushback on mask mandates in conservative places both illustrated the profound lack of trust in almost every American institution. I struggled to make sense of what I was seeing; try as I might to set aside my preexisting political opinions and keep an open mind, I found myself confronted by the age-old liberal question of why it seemed like so many poor people vote against their own self-interest. These solo road trips often made me feel like something of an investigative reporter as I counted and recorded tallies of the number of political yard signs I saw for president, Senate, and other races taking place wherever I happened to be driving on a given day. Armed with my ground truthing data, I could better make sense of the news stories and polling figures that the political commentators far away were chattering about.

Most of the books I’d read in high school and college were either solidly left or center left in their orientation. While this reading menu fit nicely into my social situations at the time, not to mention the prevailing cultural attitudes of the Obama years, I found that authors on the center right had perspectives which were incredibly helpful in better understanding the places where I found myself now. Reading about familiar political issues – whether taxes on small businesses or immigration reform or the murky lines separating church and state – from a point of view I’d previously dismissed out of hand fostered more critical political thinking than I’d ever done before. In the same week, I listened to books from voices as diverse as Naomi Klein and Ben Shapiro, or Howard Zinn and Helen Pluckrose. How few other people shared my thirst to learn from both sides wasn’t lost on me. This potent combination of traveling and reading coalesced into a remarkable moderation of my political opinions over the course of a year when it seemed that everyone else was digging in their heels and writing off the other side as a group of crazies at best and blood enemies at worst.

The emotionally and politically charged summer and fall came to an end with a nail-biter of an election in November 2020. I’d been driving in Pennsylvania a couple of days earlier, and the sight I witnessed driving into Bethlehem in the pouring rain astonished me. Hundreds of people in raincoats on the sidewalk downtown were holding signs proclaiming “Honk for Biden,” and cars outfitted with Biden-Harris 2020 flags flying from open windows –– all this in an old steel town that so many pundits had called fertile ground for Trump. In light of all the time I’d spent reading the political landscape around the Midwest that summer, I decided to predict the final vote margins in each of the swing states. I managed to beat most big-name political analysts, affirming my belief that important parts of political analysis are lost when it’s done from a cubicle far away without any time spent on the ground. On my drive back to Denver from Christmas with my parents in Chicago, I visited the U.S. Center Chapel in Smith County, Kansas, just a few days after the Jan. 6 incident. Prayers for healing a divided America, of which this chapel marked the geographic center, lined its walls. A month later, the chapel made an appearance in a Superbowl commercial promoting the message of coming together amid our political divisions and a devastating pandemic. Could the country I wanted to visit every corner of come together and heal?

U.S. Center Chapel, Kansas. Photo by the author.

As the election receded into the rearview mirror, I had to decide whether I really wanted to keep visiting places in rural America with gusto, or whether the past year had just been an unconventional detour into investigative journalism. Most of my travels had been in the Midwest, where I’d visit family and work remotely, and around the West, where I’d visit national parks and other outdoor recreation sites. With the low hanging fruit gone, I faced the more difficult (and expensive) proposition of traveling to counties in states on the East Coast and in the broader South. Did I really want to do this? Wouldn’t it be scary driving through the hollows of West Virginia and the bayous of Louisiana alone? Would all of the time and energy this would entail be better spent getting more involved in my local community rather than in examining differences between places? A piece of wisdom from one of my first managers, noting that people are generally rewarded for going deep rather than broad in their careers, gave me pause. What could be broader than going to 3,143 different places rather than working to become an expert in just one of them?

But I knew in my heart that I wanted to. Almost needed to. As I stared at the orange highlighted map on my desk, I found myself trying to solve the ultimate Traveling Salesman Problem. How could I travel to more than half of the counties in the country while minimizing the amount of time I had to spend away from work and friends, all in a way that wouldn’t bankrupt me? To control my wanderlust impulses, I settled on a rough budget that I’d try my best to stick to for the coming years: $10 per county I traveled to. This would be spartan to say the least; it assumed bargain airfares (usually on Frontier, which flies nonstop almost everywhere from Denver), cheap accommodations (lots of nights at the Motel 6, Econo Lodge, and Days Inn), and low costs for rental cars and gas. I plotted out theoretical routes across county lines linking together parks and historic sites, drawing up an arsenal of potential itineraries I could jump on when one went on sale. Slowly but surely, the map began to fill in.

“Why would you ever want to do that?” was the pointed reaction I got from one of my friends when I casually mentioned my new travel goal. Struggling to formulate a reply, I quickly realized that explaining exactly what I was doing, let alone why I was doing it, when I skipped town twice a month for a few days might get uncomfortable. I was also superstitious –– would claiming that I was going to accomplish this feat jinx it? The inherent danger of driving on roads in West Texas (among other places) in a small sedan while surrounded by big trucks and vehicles servicing the oil fields of the Permian Basin wasn’t lost on me.

“I don’t think you should tell your parents until after you finish,” one of my best friends gently suggested when I first told her about it over coffee in Chicago. “But I think you should do it – how many people can say they’ve literally been everywhere?”. Not wanting to get ahead of myself, or disappoint myself if I couldn’t follow through, I decided not to broadcast my goal to many people. Instead, whenever I faced questions about why I was flying off to Buffalo or Bismarck or Baltimore for a long weekend, I told them that I was going on “a tour of the forgotten places of America.” Which ended up being true enough. In hopes of both discovering and better understanding the country I called home, I set off to discover the places that F. Scott Fitzgerald once famously called “the vast obscurity beyond the city, where the dark fields of the republic rolled on under the night.”

Danny Zimny-Schmitt holds a Master's degree in geography and works in the renewable energy industry. When he's not traveling, he enjoys reading, running, and advocacy work for local nonprofits. He lives in Denver.

Paris, Kentucky. Photo by the author.

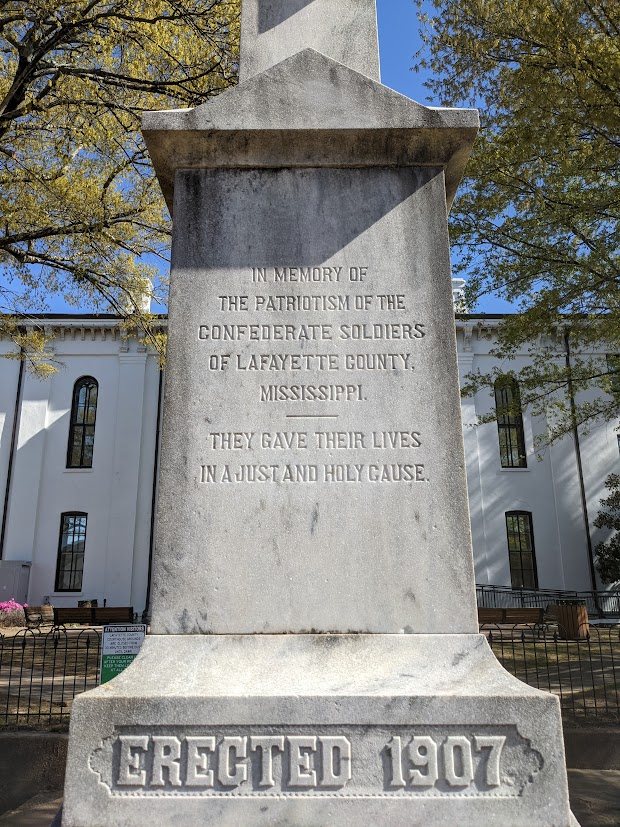

Oxford, Mississippi. Photo by the author.

In the car-dominated culture that is America, meeting the people who do not travel by car can be an important exercise in humility. While my bus idled at the terminal in Atlanta on one of my Greyhound trips, a man announced he was a “fuck up” to everyone onboard. “Now there ain’t nothing wrong with being a fuck up,” a voice some rows in front of me responded.

At the bus station in Dallas, I made conversation with a passenger bound for Seattle via El Paso and Los Angeles as we collectively struggled to understand why our bus hadn’t been announced yet even though it was past time. A few minutes later, I found myself as confused as the other passengers when the driver of our bus appeared in the terminal after our scheduled departure saying she was ready to leave with an empty bus. No one had even told us we were allowed to board yet. When we finally got rolling, my trembling seatmate asked if he could borrow my phone to call his sister in Abilene to come pick him up. “Are you a Christian?” he asked me after ending the call and handing back the phone. I figured there could only be one correct answer.

Taking the train allows for a much more up-close-and-personal view of America than major highways do, since so many towns grew up along the railroad tracks. There are some vistas you can only get from the large picture window of a moving train, whether the breathtaking views of the central California coast far from any nearby road, or the up close and personal views of forgotten places in the urban landscape. As I rode the train overnight from Chicago to New Orleans, my quiet seatmate piped up once we were weaving our way through the outskirts of New Orleans. “See that building?” he asked, pointing to the right angular concrete building sliding by outside our window. “That’s a prison,” he said. “And I’ve seen the other side of those walls,” he continued, shaking his head. I counted my blessings and wished him well as the conductor came on over the intercom to announce our impending arrival.

I often questioned whether it was my quest to travel to every county that motivated me to keep reading about perspectives I hadn’t yet been exposed to, or whether it was my reading and zest for learning that convinced me to keep driving and see places so different from the ones I’d spent most of my life. With a few more years of hindsight, it’s easy to see that this amounted to a positive feedback loop, with one continually pushing the other. There were multiple moments when I found myself listening to a book describing a social movement or political event that had taken place in a city or town that I’d driven through the day before or had plans to visit the following week. I felt especially alive in these moments, ascribing historical and social meaning to the places and landscapes through which I drove in real time.

Even as I settled into a rhythm on my frequent trips, there was no shortage of new things to observe outside the rental car window. I noticed mountaintop removal mining on national forest land in Appalachia (which I hadn’t realized was legal) and observed how they love to name bridges in the South after people in a way they don’t feel the need to elsewhere. I saw tall burial mounds built by Native Americans in Mississippi and ogled at the snow-capped volcanic peaks in the Cascades. I found that Sunday afternoons and evenings were perhaps the best time to visit a new city or place and see locals interacting with the place where they live; city parks and vibrant Main Streets were always teeming with people on Sundays with pleasant weather. With more and more time on the road, the small towns I saw in places as different as Michigan, Oregon, and Tennessee began to blend together in my memory.

Planes, Trains & Automobiles

Parkersburg, West Virginia. Photo by the author.

There were a few mishaps along the way. My tire went flat in the middle of the Nevada desert, and after calling Enterprise from outside a combined gas station and strip club to ask for a replacement, I ended up having to spend the night in a small desert town because of how long the wait for a tow back to Las Vegas would be. A second flat tire stopped me and a friend who was tagging along in our tracks on a poorly maintained county road in Appalachian Kentucky. I may have never felt more like a stranger in my own country than when we tried to order lunch from a roadside restaurant while waiting for a tow; neither of us could make out the thickly accented words of the man telling us what was on offer. We eventually resorted to pointing at our menus and confirming three times. I did get two speeding tickets, one in what was clearly a speed trap in a small South Carolina town (I don’t think my rental car’s New York plates helped my case), and the other when one of my favorite songs came on the radio and I found myself going 11 miles over the limit just as a county sheriff in Ohio passed me going the opposite direction.

There were also the numerous gametime decisions I had to make when conditions suddenly changed. When some heavy rain started falling as I climbed into the Ouachita Mountains in Arkansas, I found myself contemplating whether the chance of hydroplaning was high enough on the county roads ahead to warrant retooling my route. When I was being tailgated by a larger vehicle and needed to make a quick turn, should I give up the turn and then backtrack? When I wanted to avoid paying the outrageous $25 for the three-mile taxi ride from the Kodiak airport into the town, should I hike the trail into town instead, despite the risk of giant Kodiak bears lurking in the woods? When the bus I was scheduled to take to Birmingham got canceled, would it be better to burn air miles to get on a last-minute flight, rent a car and drive there myself, or just cancel the rest of the trip and come back for the counties I’d missed another time? This type of under pressure decision making infused a sense of adventure into many of my trips.

The most difficult and expensive part of a journey to every county in America is getting to the 30 boroughs and census areas of Alaska, most of which are not on the road network. I devised a two-week plan one July to visit the two-thirds of them I hadn’t already seen on a family cruise to Denali at the end of high school. For the first week, I traveled with my mom to national parks around the state, from Lake Clark in the south to Gates of the Arctic in the north, along the Dalton Highway of “Ice Road Truckers” fame. During the second week, I got a weekly rate at a hostel in Anchorage, took the city bus to the airport each morning, and flew out and back to Bethel, Nome, Adak Island, and other dots on the map in the Alaskan wilderness. Alaska Airlines thankfully flew most of these routes, allowing me to leverage credit card signup bonuses to use miles to pay for the majority of these flights. While there were a couple of places Alaska didn’t fly (the expensive flight on Ravn to Kusilvak Census Area remains the most I’ve ever paid for the pleasure of visiting one county), I was surprised to see how many places in the remote backcountry were tied into the wider world by just a short flight to Anchorage.

There were some constants I noticed no matter where I was traveling, perhaps most notably the post office. In every town and hamlet, from those in Alaska without roads to those on barrier islands on the Atlantic seaboard, blue mailboxes and American flags reassured me I was still in the country I call home. Another constant was the visible social status hierarchy on the landscape. Small cities had good and bad sides of town divided by railroad tracks or industrial districts just as big cities did, and even downtrodden small towns in Iowa or Pennsylvania usually had a few newly constructed houses on their perimeters where local elites presumably lived.

Different geographies changed the shape of what local recreation opportunities looked like, from mountain sports in Idaho to boating in manmade lakes in North Carolina, but it seemed clear to me that people everywhere found a way to recreate in their surroundings. Everywhere, too, the past competes with the present for space on the landscape and in the hearts of people. As William Faulkner reminds us, “The past is never dead. It’s not even past.” But because some places see more or less new construction that can erase evidence of the past, said past can loom larger in places like Mississippi than it might in New Jersey.

I find it important to acknowledge that, despite my outward act of living a poor man’s life of budget hotels and grab-and-go food on the road, making these trips was a reflection of the many privileges I enjoy. There is a certain privilege in having a salaried, high five-figure job that allowed me to work remotely from anywhere in the county. There is a certain privilege in being able to drink a hot tea at a café next to the Bering Sea in Nome in July and then sip an iced coffee looking out at the Straits of Florida in Key West a few months later. There is a certain privilege in traveling as far as Kansas and Nebraska to compete in small-town triathlons, let alone traveling as far as the backroads of Vermont and the Hawaiian Islands. There is a certain privilege in being able to travel to any county in the country and not having to worry about unfair treatment from law enforcement because of my skin color. There is a certain privilege in driving through the cotton fields of central Georgia and not having to emotionally grapple with the fact that my ancestors may have labored in this very place under inhumane conditions. While I might minimize my spending of the roughly $25,000 or so I did in service of this goal as amounting to something like $450 a month over these years (which I saw peers my age spending on nicer apartments or fancier cars), I understand that $450 a month over a few years is serious money to the vast majority of people, perhaps especially in the places I was visiting.

Copyright © 2024 The Hart & The Cur

Key West, Florida. Photo of the author.

One of the first things I learned spending more time driving on state and county roads was how effectively interstate highways function as tunnels to minimize interaction with the places they pass through. Long gone were the days of Jack Kerouac, and the requirement of having meaningful social interaction with the communities in between. This was exemplified by an important divide I noticed between towns adjacent to interstates and those far away from them: A town next to an interstate exit is often complete with the familiar brands and services travelers have come to expect from and associate with rural America, but that rural places far away from interstate corridors lack. I could drive dozens or even hundreds of miles before encountering the next Love’s, McDonald’s, or Comfort Inn on days I was far from the interstate. The economic and cultural isolation of these backroad places, whether they be in Alabama, Maine, or Montana, felt real. Without the logos and color schemes marking them as quintessentially American, these counties and towns could feel almost like a foreign country.

Two general archetypes of small-town America became evident. In the first, visible economic distress was evidenced by the vacant storefronts and buckling sidewalks devoid of pedestrians. On their outskirts, a Dollar General with a freshly paved parking lot and a rundown gas station sat across the road from each other. In the second, evidence of a Main Street revitalization program was visible in the restored architecture and stable or thriving local businesses, which often perched rainbow flags in their windows. On their outskirts, you could often find a Starbucks and full-service grocery store. Sadly, there were far more of the first archetype than the second. With so much disrepair and rural poverty on display during many of my days on the road, it was hard for me not to ponder a harsh question: When had we decided that we would let so many places in our country fall into such a sorry state, leaving so many of our fellow Americans in places where economic and social opportunities available to young people all involved leaving their homes and families behind? Many of these places felt more like internal colonies, where extractive industries like timber or oil and gas provide some of the only decent paying jobs, than what you’d expect from one of the most advanced economies in the world.

To get a better sense of the storied social tapestry of wherever I was traveling, I made a habit of stopping to read the plaques displaying stories about the area’s history at roadside pullouts and county courthouses, which often detailed stories of the railroads that first brought European settlers to the area and the surnames of the first families who farmed the surrounding land. I eschewed listening to my Spotify some days in order to tune into local radio stations; instead of the pop music and left-leaning news radio I was accustomed to in cities, I found the airwaves to be teeming with Christian rock, country hits, and evangelical preachers. While I had expected this, the extent to which it rang true and reality mimicked the caricatures surprised me. In Chicago and Denver, it’s easy to forget just how important Christianity is to the places in between. From the barrage of billboards proclaiming the sanctity of unborn lives to framed quotations hanging from the walls at small town coffee shops –– “All I need today is a little bit of coffee and a whole lot of Jesus” proclaimed one –– the Christian soul of America could not be ignored. With every thousand miles I drove, I found myself more inclined to try to understand why these places were so different and less inclined to cast sweeping moral judgments.

Pursuing that understanding led me to embrace what would become my primary companion on these road trips: audiobooks. In a nod to what I knew I could learn from each, I’d often pause the audiobook as I drove past the reduced speed limit signs on the edges of towns, only to flip it back on once I was on the other side of the municipal limits. And there was a lot to learn from the landscape; America’s built environment indeed was the paved-over paradise or hellscape (depending on your persuasion) it has the reputation for being, although some places have made notable improvements to make the built environment less actively hostile to pedestrians. Most of all, I treasured the opportunity to just observe the unbridled spirit of the places on the other side of my windshield without the charged commentary of someone suggesting I see a place through their eyes rather than my own. While driving some of the most barren landscapes in the country, whether in Wyoming or the Oklahoma panhandle, I came to understand that even if all places are not created equal when it comes to scenic beauty or cultural vibrancy, every place is home to someone, which needs to be remembered and respected.

There were plenty of surprises out on the open road. I showed up at one small-town Texas art gallery, and the woman working there, full of Southern hospitality, insisted on giving me a tour to show off the works of local artists, thrilled to hear that a city boy had wandered so far off the main drag. Many observations perplexed me, like the half American, half Confederate flag flying in someone’s front yard, or the pro-life billboards hiding behind the billboard announcing there was a Lion’s Den at the next exit. In towns in the south, a historical marker celebrating the contributions of local Black musicians or businessmen might sit right next to a monument commemorating the Confederate soldiers from the county who had died for “a just and holy cause.” A sign in central Wisconsin declaring the farmer’s opposition to a proposed confined animal feeding operation sat right next to a sign for Trump, whose administration would presumably be on the side of the operation’s developer. America could be so enigmatic when she wanted to be.

On the Road

I would be remiss if I didn’t briefly discuss what traveling to literally everywhere in the country had taught me about what its future might hold. It’s no longer newsworthy to remark that America is politically polarized and appears to be teetering on the edge of multiple crises at once; it is simply taken as fact. And of course, this is correct. But what, if anything, can be done about it, when neither political party can muster the support needed to break the gridlock?

One trend I began observing from the very beginning of my travels was the yawning economic and social divisions between the largest metro areas and smaller and mid-sized cities. While I am too young to recall the heydays of smaller cities like Altoona or Oshkosh or Pueblo, it feels that the economic forces contributing to the widening gulf between smaller and larger cities nearby are still at work. A small-city mayor I met at an advocacy conference termed these larger metros the “NFL markets,” and spoke about how difficult it is to attract younger, talented workers to places with less perceived economic opportunity. This is reminiscent of the growing divides between the small number of “superstar cities” (to use economist Richard Florida’s parlance) and the rest of the country, which I see as dangerous. As people with real political and economic power live in fewer and fewer places and are increasingly disconnected from the people and places which they rely on for their wealth, the social contract grows weaker.

Between study abroad and other travels, I’ve spent a decent amount of time in Latin America, and worry that the U.S. is experiencing a slow Latin Americanization of social, economic, and political relations, where the wealthy are disconnected culturally and geographically from the poorer masses, and democratic participation rarely yields substantive political change. The omnipresent fences around private property, declining investment in the public sphere, and widening social chasms already seem to accurately characterize America over the past couple of decades. These trends must be arrested if we want to avoid a future where a select few are soaring above and many more are being flown over.

The other concerning observation I’ve made is how much less likely people in white collar jobs are to leave their homes and interact with people in their own communities post-pandemic. Of course, this has been enabled by widespread working from home and the proliferation of food, grocery, and Amazon-like delivery services in the name of convenience and work-life balance. But when people no longer see each other in the public sphere and no longer interact with their neighbors or coworkers, bubbles grow thicker. While we may enjoy our highly curated spaces, we should remember Toni Morrison’s quote that “all paradises and all utopias are defined by who is not there, by the people who are not allowed in.” These harder boundaries in turn create a growing space for commentators and demagogues to feed their followers half-truths or outright lies about whichever groups they would like to discredit or demonize. With fewer opportunities to engage in banter about the issues of the day with neighbors, coworkers, or other acquaintances, a growing void exists that influencers and politicians will fill in service of their own interests, often to the detriment of our wider society.

Is there an antidote to these formidable economic, social, and resulting political divides? The only one I can think of that might work is incredibly simple and incredibly difficult all at once: everyone really needs to get out more. Not just to have a beer with their friends who already have an established place in their curated lives, but to make a real effort to humanize those who we don’t have much in common with, those who may not be allowed in, as Morrison says. We as humans aren’t very good at making this type of effort, preferring instead to retreat into our comfortable cocoons of familiar people rather than people who we might disagree with. But how can we reasonably expect the situation in our country to get any better if we see our fellow countrymen and women as worthy of our contempt rather than worthy of being listened to? If you believe you are worthy of being understood rather than condemned, can someone else not reasonably expect the same from you? I am heartened by the fact that groups already exist with this end goal in mind, but worry that they are fighting against stronger currents pushing in the opposite direction.

If I learned just one thing from crisscrossing America over the past few years, it’s the importance of humility and of humanizing others. I’m not suggesting that everyone needs to go out and travel to every county in America, but I am suggesting that we could all––myself included––do a better job of checking our own biases and blind spots before claiming moral superiority over others. While we aren’t good at doing this, we can either voluntarily come to the table to compromise, or we can have the consequences of not doing so forced upon us. We’d all do well to remember an astute observation from Mark Twain, which today feels a lot more like a pointed warning than a lighthearted quip: “It ain’t what you don’t know that gets you into trouble. It’s what you know for sure that just ain’t so.”

My multiyear county counting odyssey does confirm my being a stereotypical millennial in the eyes of older generations, as someone who doesn’t collect things but rather collects experiences. The most important experience I’ve collected on this journey was coming to appreciate that there is a whole lot out there that I don’t know, but that by crossing paths with so many people in so many different walks of life in so many different places, I can at least build a scaffolding for understanding, even if it takes a lifetime to build out each of the rooms.

When I was in high school, I met a recruiter at a college fair who told me that the point of going to college wasn’t so much about the degree program as it was about learning how to think. It’s now been just over a decade since I left home and started college, and while his words felt like a mystery to unravel then, they make perfect sense now. I’m not sure if I’m the youngest person ever to complete this travel feat –– the Extra Miler Club told me they don’t keep track of members’ ages –– but I have a feeling I might be. While I still do wonder whether I may grow to see this adventure as a squandering of my time and energy, not to mention money and carbon emissions, for now, I will call this journey of more than a hundred thousand miles something else: an education.

At 6am, I drag myself out of bed at the Microtel in Stillwater, Oklahoma to silence my alarm. I slip on the jeans and flannel shirt I’d laid out the night before, and find cereal in plastic containers and sugary muffins in the motel’s breakfast area. On the television overhead, the local weatherman is discussing the risk of tornadoes later in the afternoon; I make note that the greatest risk lies a bit south of my planned route for the day. After pouring coffee in a Styrofoam cup, I jump in the front seat of my rental Nissan Versa and drive west just as the sun peeks above the horizon in my rearview mirror. The rangelands of western Oklahoma open up before me on the long approach to Black Kettle National Grassland, the westernmost point of my trip for the day. Following the handwritten turn-by-turn directions I’d prepared the night before, I get on a state highway heading north and east toward a line of unvisited counties on the map. Driving east, the vegetation gradually returns to the landscape and towns begin appearing more frequently.

The audiobook I have queued up on the car’s Bluetooth for the day is The Great Reversal: How America Gave Up on Free Markets by Thomas Philippon. As the author lays out his argument, about how an insufficient number of competitors leads firms to charge artificially high prices, I surmise that this issue is more than likely to be worse in rural areas than urban ones because there is less competition to begin with. There’s no good reason why that Valero station yesterday should be able to get away with charging $3.69 for a tiny bag of trail mix. In Ponca City, I stop at the Standing Bear Museum and Education Center to walk through an exhibit detailing the tragic story of the Ponca chief Standing Bear, whose tribe was forcibly relocated from Nebraska to the Indian Territory in the late 1870s. The gravity of living in a settler colonial state hits harder at these sites than it does when I read the more ubiquitous signs erected by the state’s historical society.

My next stop comes just over an hour further east in Bartlesville, a mid-size town that’s home to the Price Tower, the only Frank Lloyd Wright-designed skyscraper. Walking the main drag, I find a more vibrant main street than I’d seen all day. After grabbing a sandwich, I continue my drive east toward the Ozarks, making a few precise twists and turns to drive through the corners of a few more counties. I notice pickup trucks hauling watercraft toward the Grand Lake O’ the Cherokees, a dammed reservoir on the Neosho River that’s evidently a draw for both tourists and locals. When the promised threatening clouds begin building to the south and east, I resign myself to the fact that I’ll be driving through a storm before making it to Fayetteville for the night. After crossing the Arkansas border, I stop at Walmart to pick up a Cobb salad and buffalo chicken wrap on the way to the Sleep Inn.

Despite the gathering darkness, it isn’t late yet, so I drive into downtown Fayetteville and find a cute coffee shop named Puritan Coffee and Beer. I grab a seat in their modern chic space after ordering an herbal tea; older adults reading books and college students on laptops sit at the tables around me. I pull out my computer and connect it to the WiFi, updating my online county tracking map to reflect the 21 new counties I traveled to that day, and check the notifications on my phone that I’d been neglecting all day. The next morning, I will drive my rental car back to the Northwest Arkansas National Airport, where I’d picked it up two days earlier. At a social event back home in Denver that evening, I’ll meet a couple from Arkansas who had their first date together at Puritan years earlier. In these moments, our big and complicated country could still feel small.

We welcome Letters to the Editor. Send your thoughts, comments, and responses to jeanluc@thehartandthecur.com. We look forward to hearing from you.